The Story of a Photograph

12th Nov 2018

Nigel Dutt is a retired computer software engineer turned photographer. He is based in Devon where he enjoys photographing landscapes, flowers, architecture, racing cars, townscapes and works of art. His work has featured in our exhibitions and he has also judged one of our bi-monthly competitions.

Nigel got in touch with us earlier this month with a lovely story about how a photographic puzzle had been solved after 75 years. As it was Remembrance Day here in the UK yesterday we thought it was fitting to share this lovely account with you.

Nigel’s father, Charles Dutt, was an RAF dental surgeon who at one time during WW2 travelled from squadron to squadron in the Near East in his mobile surgery. He was a keen photographer who always carried a Rolleiflex camera and he also did quite a lot of flying as 2nd pilot or passenger.

“He kept all his negatives, so a while back I scanned hundreds of them in and put them on Flickr,” says Nigell.

His father had a wartime photo album in which there is a page dedicated to Squadron Leader John Gilliard DFC, featuring an in-flight photo of the pilot taken from behind and a series of shots of the ground they were passing over.

Looking at his log book, Nigel learnt that this flight with the then Flight Lieutenant Gilliard was from RAF Shallufa on Feb 15th 1942 in a Hart aircraft and is logged as a local flight of 45 minutes duration.

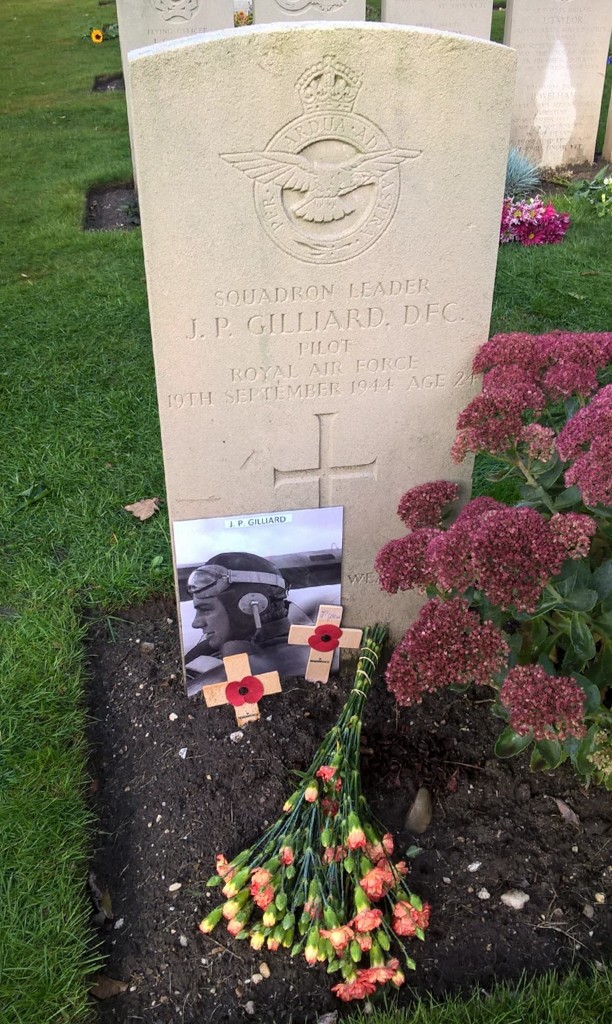

“Searching for information about John Gilliard I found that he died in Sept 1944 over Arnhem in the Netherlands when his plane was seriously damaged by enemy fire. He ordered his crew to bail out but, along with his tail-gunner, he failed to escape himself and went down with the plane. He had married earlier in the year to Cecilie who had only just given birth to their son, John, when he died. He was 24.”

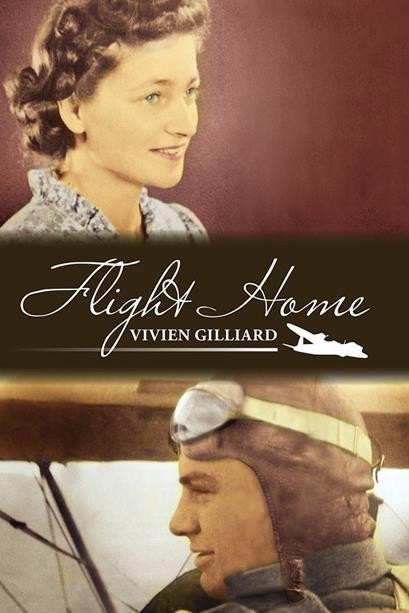

On further searching, Nigel came across a recent book, Flight Home by Vivien Gilliard and was very pleasantly surprised to find a modified version of his father’s photo of John on the front cover.

“I contacted her,” says Nigel “and it transpired that a print of the photograph was always displayed on her mantelpiece by John’s widow Cecilie. Vivien is married to their son John, who in turn had kept and displayed the photograph after his mother died. Nobody knew anything about the photograph such as when and where it was taken and by whom, so the family was delighted to hear the story behind it after so many years.”

It was when searching Cecilie’s attic that the family found a box containing their letters and that was the genesis of Flight Home. Sadly, there was only one other image of the adult John, in a somewhat blurry group photo where he is one of several RAF people.

John G at Port Suez

Charles D at Port Suez

After sending Vivien a link to his father’s other wartime photographs, she quickly identified one of John taken at Port Suez, and it is accompanied by a matching photo taken of Nigel’s father at the same spot, presumably by John. “Unfortunately, not only does John have his eyes closed because of the sun, but that negative has suffered over the years much more than the one of my father” says Nigel.

He even found the old envelope from Nasabian’s photo shop in Cairo with the order to make two enlargements of the flying photo. “These enlargements are the one in my father’s album and the one that spent all those years with Cecilie and John junior,”explains Nigel.

John Gillard

John Gillard

The book-cover illustration was based on Cecilie’s print, and the artist had removed the intrusive vertical bar from the windscreen. However, Nigel then found that he had overlooked another photo taken by his father at the same time where the vertical bar of the window covers John’s face but reveals the part of his flying helmet that the main photo covered, which, unlike the artist’s impression, shows an earpiece for the intercom.

“Being a Lightroom rather than a Photoshop user,” says Nigel “I had to do a quick bit of ‘teach yourself Photoshop’ and merged the two photos to produce a more realistic shot of John, I know I can improve on this merge but that’s for another day.”

Needless to say, this version of the photo was very much appreciated by the family, and they had a copy printed and laminated so that it could be placed on John’s grave at the annual memorial event.

The Dutch still honour the men who died on the failed operation Market Garden at Arnhem, and it was local people who placed the photo.

What a lovely story this is and thank you so much Nigel for sharing this beautiful account with us. We’re glad that the puzzle was finally solved after so much time.